Arkylie Teaches Hiragana

Ready for the basics?

Focus and Teaching Style

My College Experience

A couple decades ago, in anticipation of my upcoming Japanese class in college, I spent a summer teaching myself the basic writing system -- both Hiragana and Katakana.

Then I got to college, and we spent the first three months just learning Hiragana. (Turns out nobody expected students to learn on their own before class even started.)

We also focused on Polite Language; casual language would come later. So the words and phrases got complicated quite fast. Which is useful if you're focused on being able to hold a conversation without offending anyone.

Focus of This Site

I'm not here to teach you the language, or the best way to say things. I'm here to teach you the most basic writing system -- Hiragana, a set of kana, or letters/symbols, that represent syllables. E.g., using some words you likely already know:

- KA TA NA

- SU SHI

- SU DO KU

- SA KE

- DO JO

From these building blocks we'll lay a foundation, allowing you to read very basic Japanese. After that, if you're interested in learning more, there are a wealth of resources available; I'm sure you'll find them.

So I'll be focusing on these aspects:

- Simple, casual wordforms

- Simple, casual phrasing

- A lexicon built around the kana introductions

- Common vocabulary

- Most basic meanings -- little focus on homonyms

(Japanese has a ton of homonyms, you don't even know.)

Note for Screen Readers

Typically I'd try to ensure that my page is as accessible as I can make it, including for screen readers, but since this is a page discussing a visual writing system, I can't see how this effort would be helpful. There are probably much better resources out there; I'm just a highly distractible creator who randomly decided to throw together a teaching page tonight.

First Set

A I U E O

English has... a lot of vowels (~20). Japanese has five.

Actually, lots of languages have five vowels roughly mapping to Japanese's set. Spanish, Hawaiian, Greek, Fijian, Samoan, Maori, etc.

English has five vowel letters (note: Y is a variant of I; they share 100% of the same sounds, just in different proportions) covering about four times as many sounds. Not only that, but thanks to the Great Vowel Shift, our vowel letters map to different sounds from the way these letters get used in sensible languages.

Let's see how the English letters map to Japanese vowel sounds:

- A as in aha! (Ma saw Pa wash his arms in the sauna.)

- I as in ski (We see a free machine.)

- U as in fu (Who ruined Sue's new blue suit?)

- E as in cafe or bet (Hey, they say Ted said it's red.)

- O as in no (Go show Jo the cold storage dome.)

(Note: My dialect is Pacific Northwest; if the following example words don't work for you, try this video for a native speaker showing even the proper mouth position.)

The E sound isn't two separate sounds, but a wider range than we use in English. It's going to shift a bit based on surrounding sounds and stress patterns (actually, this is going on with the other vowels as well), but there's no minimal pair where meaning gets determined by whether E sounds more like THEY or more like THEN.

With one exception, every syllable in Japanese is based on one of these five vowels, either by itself or after a single consonant. The only exception is N, which can exists as a syllable by itself (as in RA ME N).

Anyway, let's get a move on!

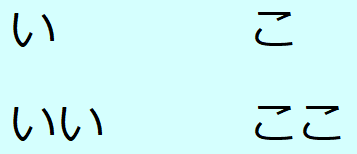

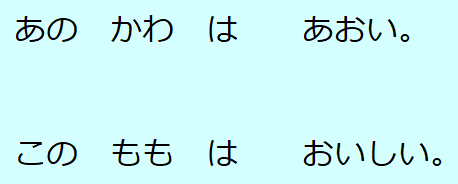

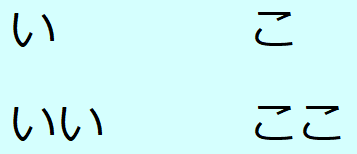

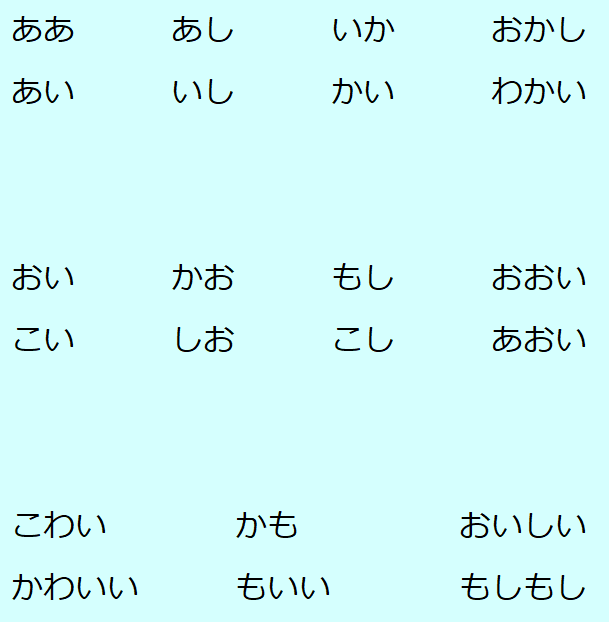

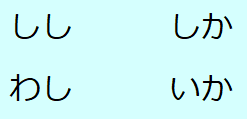

Two simple kana: I (pronounced like in "ski") and KO. Each makes a word if you double it. Read these:

The words in question are "good" (II) and "here" (KOKO).

Two more: SHI and MO. Again, they form words from simple duplication:

The words are "lion" (SHISHI) and "peach" (MOMO).

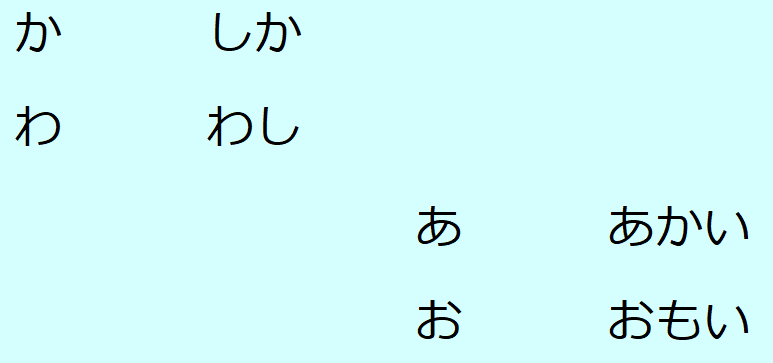

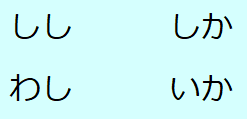

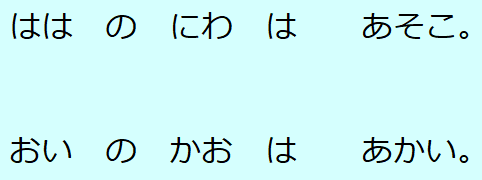

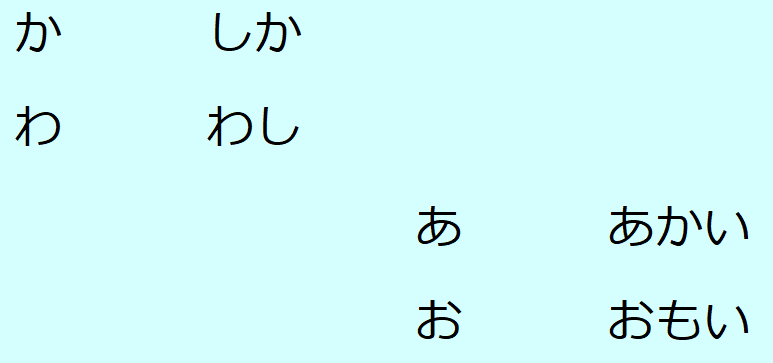

Now let's try two more pairs. Here we have KA and WA on the left side, then A and O on the right:

Could you read all the words? The words are "deer" (SHIKA) and "eagle" (WASHI), then "red" (AKAI) and "heavy" (OMOI).

But there's a bonus! Read down the letter introductions to get "river" (KAWA) and the simple form of "blue" (AO -- the full form is AOI, like with AKAI).

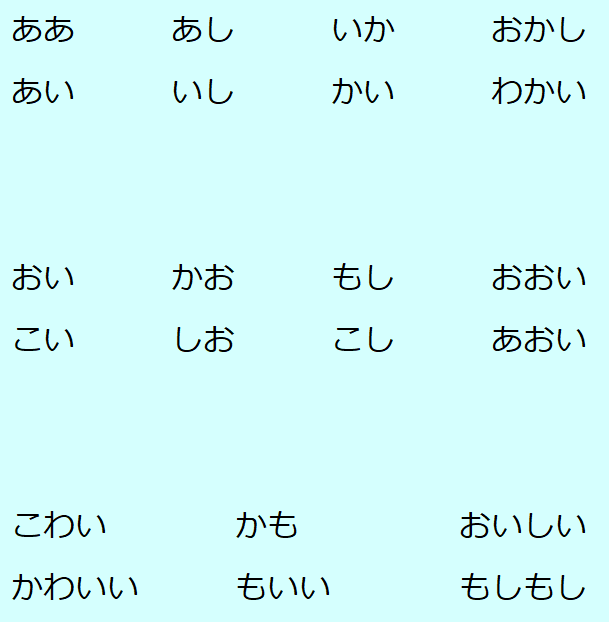

Now that you've got eight kana to work from, it's time to practice sounding them out:

How's that feel? The connection between the symbol and the sound starting to make anchors in your brain?

But what do they mean?

I'll discuss the meaning of the words in pairs, and you get to find them on the chart! Or write them down, if you prefer. Here goes:

- AI and KOI

- Two different words for love; AI is the more general term, KOI more specifically romantic love

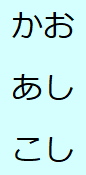

- ASHI and KOSHI

- The words for "leg/foot" and "hips/waist" (the Japanese make no distinction for those pairs)

- OI and OOI

- The first means "nephew"; the second, "a lot" -- vowel length is a distinguishing characteristic of Japanese!

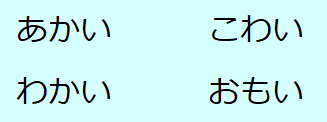

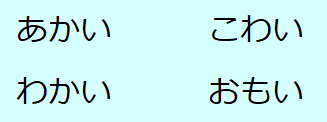

- KAWAII and KOWAI

- Ah, the bane of the newbie! The slightly longer word means "cute" but the shorter one means "scary". Don't mix up the A/O part, and work on those lengthened vowels!

- SHIO and OKASHI

- The words for "salt" and "sweets" (as in candy or confections), which can also be said just "KASHI". Care for a song about going to The Land of Candy? Listen for the phrase "Okashi no Kuni"!

- OISHII

- Might as well give you the word for "delicious" as well!

- AA and OI

- Exclamations! "Ah" and "Oi!" And yes, that's the same word as for "nephew"

- IKA and KAI

- The words for "squid/cuttlefish" and "seashell"

- WAKAI and AOI

- You should already know one of these from earlier in the lesson; the other means "young".

- MOSHI and MOSHIMOSHI

- The longer term is how you answer the telephone; the shorter one means "if"

- KAI and KAO

- We already covered one of these; the other means "face". Do you see a face in the seashell?

- ASHI and ISHI

- We already covered one of these; the other means "stone". Are your legs made of stone?

- KAMO and MOII

- The first can mean "a duck" or "possibly", so try remembering the phrase "it might be a duck." The second is a way of saying "it's okay to [do X]", like "It's okay if you eat that" or "It's okay if you use that" (see here for a discussion of the grammar)

(For those who skipped the meanings, I'll introduce the words as they get used. No worries.)

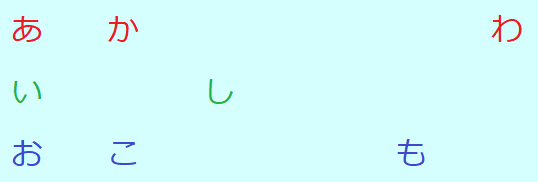

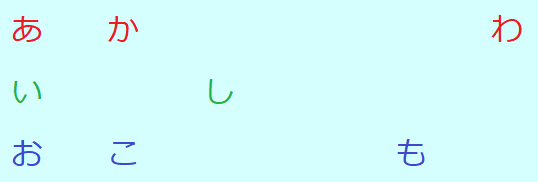

By now, you should be able to recognize eight kana: A I O - KA KO - SHI - MO - WA. Let's put them in a chart:

The colors show which vowel is being used (red for A, green for I, blue for O).

Time to Practice?

It's always a good idea to stop and cement things in your head in different ways before you get overwhelmed with incoming data. Here's some ways to practice the kana you've just learned:

- Flashcards

- Here's a site with flashcards -- just print them up, find the eight we've just gone over, and practice sounding them out. Or try to make the words we've gone over so far!

- Handwriting Example

- Have a video showing good form for the handwritten versions. It's actually kinda satisfying to see the nice brushwork and clear forms take shape.

- Handwriting Practice

- If you're ready to start writing the letters yourself, print up some practice sheets and go to town!

Then again, maybe it's time for a break? Why not listen to Hakuna Matata in Japanese? This one's got nice subtitles showing not just the Japanese but the sound (transliteration) and the English translation. You might even be able to pick out a few of the words you've just learned!

.oOo.oOo.oOo.oOo.oOo.

Second Set

Gimme a Refresher!

If you've already gone through the meanings of the words in the first lesson, figure out the categories for these sets. If not, just read the kana! You can always backtrack to the first lesson if you need a little more time to get the anchors straight.

Group A

Animals!

=^..^=

Group B

Body Parts!

=^..^=

Group C

Things you can eat!

=^..^=

Before making your guess, see if you can spot the pattern in this last group here.

Group D

Adjectives!

Each of these words ends in I. That's typically how you pick up on Japanese adjectives

(although it's not the only form of adjective).

Apparently there are about 500 I-form adjectives, and you can study them here if you like,

grouped in sets of 10. Maybe just see how many kana you can pick out!

=^..^=

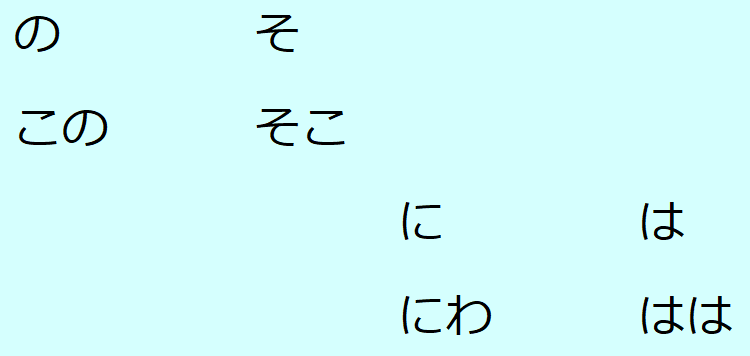

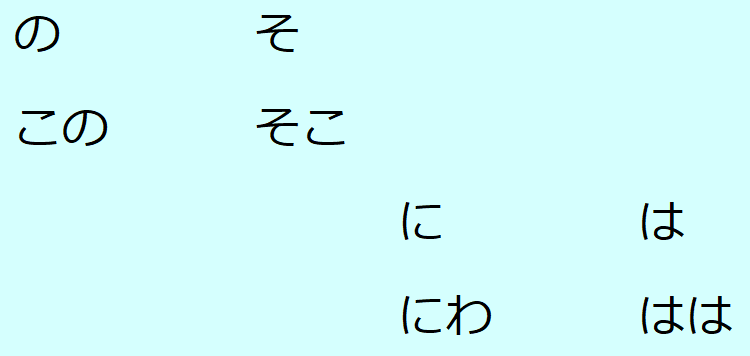

All righty, let's get a move on with NO, SO, NI, and HA:

The words given are "this [X]" (KONO), "there" (SOKO), "garden" (NIWA), and "mom/mama" (HAHA).

...yes, yes, laugh at your mom, go ahead.

Remember, this is the casual way to refer to your mother. You wouldn't say this to her face! Think of it like when you're describing your mom to your friends.

Three of these kana have a special usage in Japanese grammar -- but more on that in a bit. In the meantime, go over those kana and really cement them in your brain:

Now find these entries on that chart:

- ANI and ONI

- Perfect for setting up sly jabs at your sibling: "older brother" (ANI) and "ogre" (ONI)

- WANI and KANI

- The alligator and the crab!

- HASHI and NISHI

- A bridge, and the word for West

- MONO and KOSO

- MONO is the general word for "thing", while KOSO can be used to emphasize part of a sentence (but that's more advanced grammar)

Lastly for this section, let's learn some of the KO/SO/A set. Where English distinguishes only two distances (here and there), Japanese distinguishes three. It's basically something near the speaker (KO-), something near the listener (SO-), and something far from both of them (A-):

KOKO/SOKO/ASOKO refer to locations: here, there, over there.

There are two groups for "this/that": One replaces the noun, the other attaches to a noun. It's the difference between "bring me that" and "bring me that box," which in English use the same word.

KONO/SONO/ANO is the group that attaches (this bridge, that bridge, that bridge over there); later on, when you learn RE, you'll be able to use KORE/SORE/ARE to mean simply "this, that, that [thing] over there."

.oOo.oOo.oOo.oOo.oOo.

Third Set

Ready to get started with a little grammar and some actual sentences?

Particles: How to Mark Word Relationships

English pronouns show whether they are the Subject (doing the action) or the Object (receiving the action): I/me, he/him, she/her, we/us, they/them. For the most part, we no longer mark this feature, because the verb separates the Subject (before the verb) from the Object (after the verb). But since Japanese verbs come at the end of the sentence, and the other pieces can be moved around fairly easily, they need to mark these roles.

But unlike English (and many other languages with more widespread case marking, like Finnish or Greek), Japanese doesn't change the word being marked; it just sticks a Particle on the end. This is a small word -- usually just a single kana -- used to mark a relationship between words. Kinda like a pronoun or an article, but a much broader category.

There's a marker for the Subject, one for the Object, one for the Indirect Object; one that marks a Destination, one that marks a Location for the action, etc. etc. etc. But that's a huge topic. For now, we're not even going to bother with Subject and Object.

We'll start with just the Topic Marker, because it's super common and because it's one of the few times when a kana makes a sound other than its normal reading. When the kana は marks the Topic, it's pronounced as わ. Pick one of these sentences to memorize for your mnemonic:

- はは は かわいい。

- haha wa kawaii

- はは は こわい。

- haha wa kowai

- はは は わかい。

- haha wa wakai

Any of those three will help cement the distinction between HA used as a normal letter and HA used as a marker (where it's pronounced WA).

Note: One way of transcribing Japanese into English letters is to just write them as they're written, not as they're pronounced in context. And most of the time this is fine, because Japanese is very regular. But this style is detrimental for the newbie, because it leads to pronunciation errors on a couple of the highest-frequency letters -- of which "HA pronounced WA" is the most prominent. Their version would be "Haha ha kawaii" instead of "Haha wa kawaii" -- see how that could get confusing?

Anyway.

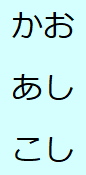

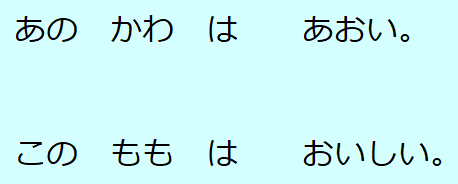

Now, you might have noticed the pattern "NOUN wa ADJECTIVE" there, and figured "Well, clearly WA means 'is' then." Which... no. Actually, the "is" part is kinda bundled up in the adjective there -- it acts like a verb! The WA part just marks the Topic, in this case also the Subject, of the sentence. So this "NOUN wa ADJECTIVE" form is one we're about to explore; see if you can work these out:

Here we have some basic statements. Each sentences describes the Topic (Ani, Oni, Ishi) using an adjective (Wakai, Kowai, Omoi). Simple enough. Let's weave in those this/that/that-over-there words:

The peach is being held by (or is at least close to) the speaker, hence the use of KONO. But since the river is presumably not near either the speaker or the listener, it takes ANO: "that river over there". How did this person describe the river?

The I-adjectives can go immediately before a noun, describing it. Here, it narrows the topic: not just any of those deer, but specifically the young one over there, that's the Topic being discussed.

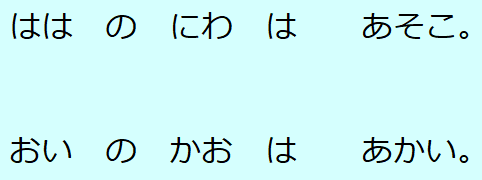

Now let's introduce a second Particle:

You know the 's that we stick on the end of nouns to mean possession? Sue's book, Jim's hair, the cat's toy? That relationship is indicated by the Particle NO.

No, seriously. It's NO.

So we have two types of possession indicated here. Mama's garden is a location owned by her. The nephew's face is a natural part of his body. But just like English, Japanese makes no distinction between different forms of possession, at least in the grammar.

So far so good.

Japanese can be written in two directions. It's typically written vertically, and read down in columns from right to left. But written horizontally, it's read just like English: left to right.